I've begun probing the FX Impact M3 for learning nuggets out ahead of my upcoming YouTube M3 tuning guides. The learning I discover, I'll share here as I go, as a resource for new tuners seeking information on how to tune the M3. Experienced tuners, please feel free to chime in and share your victories too. Tuning is as much an art as it is a science. There are many good tuners out there and many good ways to go about it.

Right out of the gate, I sought an easier approach to tuning the M3. One which would streamline my time in the chair and reduce pellet consumption along the way. My previously published YouTube tuning guides on the

Maverick,

Dreamline,

Crown Continuum,

Avenger,

Avenger Pup,

Redwolf, and

Atomic taught me that

perfect tune searching can be taxing on both the soul & pocketbook, so coming up with an "easier way" for

this new guide has been a priority. Side note: Going forward, AEAC Tuning Guides will be published on the main channel,

AEAC Home, and no longer on

AEAC Vlog.

Right out of the gate, I ran a baseline chart for the M3 Compact (300cc bottle & 500mm liner) to see how Sweden had set it up. The takeaways for me are that Sweden likes a 90 bar reg for good all-around power & efficiency with an 18gr out of this configuration. That's important to note as we go forward and explore the lower limits of the aft reg on the M3, and lighter ammo. From the below, it's also clear that they like the gun set up with the Power Adjuster (PA) on 16, presumably because this is what the majority of their customers want. Personally, I've always sought to tune the FX's to more of a "middle point" on the wheel. Below is my M3's baseline run as it came out of the box.

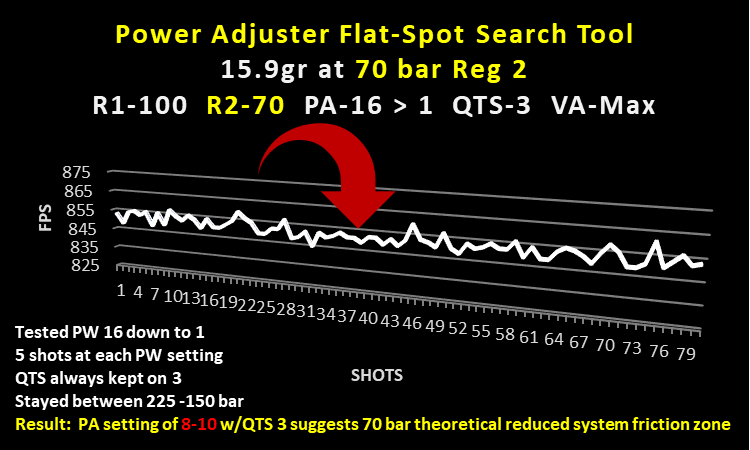

After running a base line, I was curious about the relationship between the PA wheel and the QTS micro adjuster, as well as how

low I could get reg 2 to run reliably. So, I came up with the below. It's a simple 80 shot evaluation of the above described and to my surprise, it revealed an interesting anomaly. If you'd like to run the test on your M3, simply take 5 shots at each PA setting (16 down to 1) while keeping the QTS reset to #3 with each new PA setting. Keep the Valve Adjuster (VA) on max-open for the run. It's also good when exploring the lower limits of a reg to keep your bottle pressure in a reasonable window like 225-150 bar or so. I've found that sometimes, regs get goofy near their lower limits (although not with this one) and can produce unreliable results when the pressure on them is at the two extremes. It's also good when running low reg pressure to allow the system a few seconds to take a breath in between shots. I like 5-10 seconds. Once done with your test, enhance your chart's magnification to around 50 fps total, so that you can see what's going on. Here's what I got:

The above test (I'm calling the Power Adjuster Flat Spot Search Tool) revealed an

enhanced performance zone between the PA settings of 8-10 when running a 70 bar reg and while shooting a 16gr. Velocity clearly ran much tighter for me in this 15-shot zone. I posted the initial results here on AGN in another post (admittedly with overenthusiasm and without a full understanding) and ruffled some member-feathers. The outrage encouraged me to slow down, consult with Sweden about the find, and take a more in depth look at this phenomenon. Sweden had the below to say when I shared the above with them... it was a phone conversation, some of which I'll quote and some of which I'll paraphrase.

These test results are "intriguing & exciting," and that you may have "discovered a hack that could be quite useful in locating a mechanical sweet spot in a gun's overall system-mechanics... a sweet spot where PW & QTS interact with a bit less resistance, hence offer enhanced performance." Sweden theorized that by running this test, one could easily locate & identify this theoretical system sweet spot, and perhaps build upon its usefulness. For now, they are calling the data "undeniable." After the holiday vacation, Sweden will run my "flat spot search tool" test in an effort to better understand it. I'll catch up with them afterwards and share what comes of it. Moving forward from the find, I decided to exploit my discovered

70 bar, 16gr flat zone anomaly and run an entire chart at that PA #9 sweet spot. I was rewarded with the below which for tracking purposes at this point, I'm calling Eco Tune 1. Bearing in mind that I had performed NO other searching around for ideal settings other than having run my initial flat spot search tool, I kinda had an oh sh*t moment and thought to myself. "Dang, that's a very decent usable shot chart... and this

flat spot search tool test could be a useful method for others to simplify M3 tuning."

Wanting to evolve Eco Tune 1 into something more field worthy, I slowly worked the Valve Adjuster in a 1/4 turn at a time, searching for further tightening of shot-to-shot velocity. This step trims any waste air, increases efficiency, and improves accuracy. As you do it, listen for the report to go from a "cough" to a "snick" or even a

light "snick-ping." The change in sound means that you're "there" and probably in an improved area. The below Eco Tune 2 is what I took into the field with me last week to 50-yard film for the upcoming tuning guide... and the results were excellent, especially for a 16gr leaving at 850 fps and arriving 50 yards sway at 675-700 fps, in a 3-7 mph wind (multiple troll-strolls included)

. Note: the VA ultimately needed another 1/4 turn in to stabilize 50-yard accuracy, which super-validates the usefulness of this nifty device.

Having validated the above methodology on film, I set out to retest my flat spot search tool again, but this time with an 80 bar reg instead of 70. The 80 bar test revealed yet another clearly visible 15-shot flat zone. Again, I exploited this enhanced performance zone to quickly & efficiently come up with another good tune for the M3. I'm calling this latest discovery, Eco Tune 3, and its numbers suggest some

serious system-harmony.

For me, this discovery and its apparent system-sweet-spot-hack has me quite encouraged. I'm very much enjoying the speed & simplicity of getting to the result, as well as field-validating the accuracy that came via the new approach. As soon as the rain clears, I'll fine tune Eco Tue 3 via the VA, then get back out there at 50 to film-validate it for the upcoming YouTube AEAC M3 tuning guides. Then, hop on the 18gr... then on to the max power extraction stuff.

As I come across these learning nuggets, I'll share them here on AGN and on AEAC Instagram, "hookedonair" first... out ahead of the video, so you guys don't have to wait.

Enjoy and happy tuning

Steve